The two gigantic tanks of the regasification plant installed in the port of El Musel, in Gijón, haven’t been used once. Building them cost nearly 400 million euros. The project was approved in December 2008, “in a context in which there were great prospects for energy demand growth in Spain”, justifies Enagás, who owns the facility. Those perspectives were never fulfilled, and the infrastructure ended up being in hibernation, which means it’s technically stopped but can easily be switched on and used if ever needed again. Enagás didn’t risk anything in the project, because their investment was guaranteed by the state, but consumers pay for its maintenance in their gas bills. According to the gas system estimates for 2019, the hibernation of El Musel will cost 23.6 million euros.

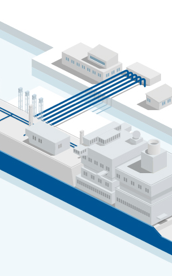

Regasification plants receive liquefied natural gas, which arrives by sea in methane tankers, to transform it from its liquid state into a gaseous one and from there distribute it to the final consumers via transport and distribution networks. The reception of gas by ship represents practically half of the fuel imported by the country. Almost all the gas that’s consumed comes from abroad, and the rest arrives via gas pipelines. In Spain there are six active plants (Mugardos, Sagunto, Bilbao, Barcelona, Cartagena and Huelva), plus El Musel. With seven in total, Spain is the country with the most regasification plants in Europe. “Everyone wanted to have one in their Autonomous Region; they were mostly planned for political reasons, rather than real need”, says an analyst.

In October 2009, a year after El Musel was approved, a methane tanker that was going towards Barcelona (where the oldest regasification plant in Spain, built in 1969, is located) was diverted towards the plant of Mugardos, in the port of Ferrol. Due to the low usage of these plants caused by methane tankers not unloading, in the Galician installation they didn’t have the minimum liquid methane necessary to guarantee it wouldn’t evaporate generating carbon dioxide emissions. That episode was repeated again, taking extra fuel from Huelva to Barcelona. And it has happened on other occasions, years later, generating an extra cost which the consumers pay for in their gas bills.

Between 2008 and 2018, the regasification plants were used, on average, at 22% of their capacity. So far this year, however, this activity has been revived. Between January and September 2019, the level of regasification has reached 71% above the average of the last five years, according to Enagás. This means they’re functioning below 40% of their capacity at the moment.

.jpg)

While the numbers make it evident that these infrastructures are oversized, something that has been acknowledged by the Administration, we still witness surreal situations. El Musel, in Gijón, is not only in hibernation, it was also declared illegal in 2013 by the High Court of Justice in Madrid because it was built at less than 2,000 metres from inhabited areas. The Supreme Court confirmed the sentence three years later, but Enagás, the company who was awarded the contract, is currently in the process of legalising it again so it can start functioning. “They are trying to legalise the plant again, starting an authorisation process, both for construction and environmental impact, so we have a situation of having to argue about where we want it to be built, if we want it to be built or, indeed, if a plant that is already built can be built or not, which is rather absurd”, explains Paco Ramos, member of Ecologistas en Acción de Asturias, while standing on a hill from which you can see the plant in the port. Ecologistas en Acción de Asturias is one of the organisations that originally argued against the power station.

What does Enagás say about the excess of infrastructure? “Infrastructure is designed for peak demand times, because if it was designed for average demand, there would be supply issues at critical moments”. In 2012, the National Commission of Energy (Comisión Nacional de Energía) admitted that El Musel was not necessary for supply.

Between January and September 2019, the level of regasification has reached 71% above the average of the last five years, according to Enagás. This means they’re functioning below 40% of their capacity at the moment.