On the La Canonja industrial estate in Tarragona there is a metal chimney that passes unnoticed among the chemical works. It is not as well-known as the Castor storage facility or the El Musel regasification plant, but it is another obligatory stop along the road of gas fiascos. It is the first combined-cycle generating plant in Spain to close for lack of demand, another sign of the country’s excessive gas-powered electricity generation capacity that still doesn’t correspond to demand.

This plant came into service in 2003 at the start of the boom in construction of this type of facility to generate electricity with natural gas. Within barely 10 years the country went from having no combined cycle power plants, to having more than 50. In the EU, only Italy and the UK have more.

The Tarragona plant (386 MW) passed through various electricity companies’ hands until it ended up with no company’s name at all on the façade. After three years with very little production, in 2016 it stopped generating electricity and in September 2017, while it was still owned by Viesgo, the Industry Ministry authorised that it be shut down and dismantled. However, this is not an isolated case and several more plants may close. Before this, permission was granted to close the Iberdrola gas plant in Castellón de la Plana although this has not taken place. Others, such as Endesa in Huelva have had their requests denied, and there are still applications to mothball at least five plants owned by Spanish company Naturgy in Palos, Cartagena and Sagunto.

“It’s a shame that it’s shut down when it seemed that this was going to be the solution,” laments Roc Muñoz Martínez, the mayor of Canonja, who says the plant is still being dismantled. “They’re selling it off bit by bit. The steam boilers were sold to another company, IQOXE, and next it’s the turbine.” This industrial estate in Tarragona employs 10,000 people and there’s a high demand for electricity at a good price, so it is particularly striking that they are dismantling this combined-cycle plant. “It was great news when it opened but when they showed me the last production schedules the plant wasn’t producing anything. How is that possible?”

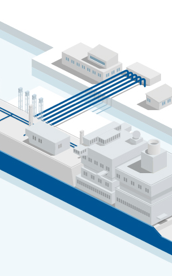

It is possible because the companies that launched themselves into building these modern, combined-cycle gas plants did not envisage the changes that tore up their optimistic forecasts. The country’s energy consumption was much lower than expected, and at the same time, the cost of renewables plummeted, making them much more competitive, especially in Spain where there is plenty of sun and wind. As a result, over the past seven years Spain’s combined-cycle gas plants have operated at below 17% of capacity (see graphic).

.jpg)

This catastrophic situation has improved significantly in 2019. Suddenly, there was an ideal scenario for these plants: low prices for natural gas, the almost total halt of coal-fired power plants and little hydroelectric power generation due to a bad year of rain. As a consequence, its production between January and September has grown considerably. But even with all this, according to data of the Spanish electricity network Red Eléctrica de España, so far this year all these installations have been working at an average of 24.3% of their total capacity.

“They could close all the coal-fired plants and half the gas ones and it wouldn’t matter at all,” says the electricity market analyst Paco Valverde. “We have the overcapacity of an Arab country or a multimillionaire. People talk about a solar power bubble but the bubble has been in the combined-cycles.”

How many surplus generating stations are there in the system? At the time of the highest national consumption on February 8 last year at 20.24h, 40,947 MW of power on demand was needed. However, the combined-cycle plants alone can generate 26,284MW, a quarter of the total installed capacity of 104,053 MW of coal, nuclear, hydroelectric, wind, sun etc. While it’s true that some of these technologies function intermittently when there’s rain, wind or sun, nevertheless as Valverde explains, the recommended security of supply cover is 10% more than the fixed (not intermittent) power needed at peak demand. “That’s to say, if the maximum that Spain needs at any one moment is 40-45GW, we need 50GW guaranteed. But the country has a lot more.”

Paradoxically, the climate change emergency means it is necessary to build many more renewables. It’s necessary to make room in the electrical system for technologies that don’t emit CO2 and cause climate change. This energy transition will lead to the gradual closure of polluting plants that will be replaced with cleaner ones, such as wind or solar power, with the least financial risk to the system.

.jpg)

Companies such as Endesa have said they intend to accelerate the closure of coal-fired power stations (the most polluting) because they are “not competitive” in current market conditions. The big question is how much longer the combined-cycle gas plants will be needed (which, although they are more efficient than other fossil fuel plants, still emit CO2 and are associated with methane emissions) while gas production is also associated with methane emissions) and how they can remain economically viable faced with a massive increase in cheap renewables.

“It’s true that Spain has an enormous excess capacity of combined-cycle generation, it’s completely excessive,” says Natalia Fabra, an economics professor at the Universidad Carlos III in Madrid. “But gas will continue to play an important role for years to come.”

If the government still hasn’t allowed the closure of more combined-cycle plants, it’s because they are considered an insurance for the electricity system in the coming years. Like a fire station: in theory you don’t want it to be busy so much as ready for action when needed. In fact, the draft Integrated National Energy and Climate Plan (PNIEC) that the Socialist government sent to the EU anticipates that between now and 2030 the coal plants and half the nuclear-powered stations will close but the existing combined-cycle ones will remain open.

Are so many combined-cycle plants really necessary in order to carry out the energy transition? As Fabra says, right now it’s difficult to know how many of these facilities are going to be needed because “it depends on variables that are currently unknown, how the country’s energy demands evolve, the extent to which sectors such as transport are electrified, the generating potential of new renewables …”

As for renewables, there has been an avalanche of requests to connect new infrastructure above all using solar power. At present renewables have a capacity of 28.9GW as of the end of August this year the REE had given permission for a further 81.7GW, an enormous capacity that suggests some speculation is involved. “We have no idea how much renewable power there is really going to be. We know about demands for access but my impression is that this is a bubble of requests and that later there will be less,” the economist said.

At the same time, all forecasts will change completely if energy storage systems are finally developed and there’s a greater integration of European energy markets, in which case all these gas-fired plants would not be so necessary to guarantee the system’s stability.

It seems clear that the government wants to maintain as many combined-cycle plants as possible until these unknowns are resolved, even if this means keeping facilities open in spite of them not being financially viable.

Repsol purchases the Tarragona plant

The combined cycle power station of the industrial chemical park of La Canonja, which is closed, is now owned by Repsol, who bought it in 2018 as part of the assets purchased from Viesgo. That particular operation had important repercussions: as published at the time by financial newspapers, the low price paid for the combined cycle power stations meant the collapse of the value of this type of installation. Specifically, Repsol would have paid approximately 10 million euros - when fifteen years ago their value was over 800 million - for the stations of Bahín de Algeciras (Cádiz) and Escatrón (Zaragoza).

“We have the overcapacity of an Arab country or a multimillionaire, says the electricity market analyst Paco Valverde